In our previous blog we spoke about the dangers of storing your data digitally and why many organisations are choosing to revert to storing their critical data on microfilm.

Today we are Going to explore the Barbarastollen tunnel, where the German National Archivists use microfilm to safeguard their cultural heritage.

The Barbarastollen Tunnel: Germany’s Memory

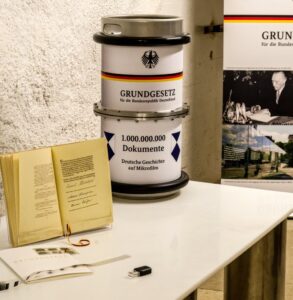

Hidden 100m below the “Schauinsland” lies the Barbarastollen, a disused silver mine that has now been converted into an underground archive of microfilmed records. It houses over 20,000 miles of microfilm, drawn from German archives, museums, and libraries.

Hidden 100m below the “Schauinsland” lies the Barbarastollen, a disused silver mine that has now been converted into an underground archive of microfilmed records. It houses over 20,000 miles of microfilm, drawn from German archives, museums, and libraries.

The first deposits were made in 1974, and four years later it became the only cultural property in Germany under the protection of the Hague Convention of UNESCO, giving it unique protection even during armed conflict. This protection is shared by only four other sites in the world. Even in war, where not only people but also their heritage and history may be targeted, the history within this vault remains protected by law. It is the rarity and cultural significance of the documents themselves that have earned this protection. Among the 900 million documents stored are:

-

- The treaty text of the Peace of Westphalia, signed at the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, granting religious freedom to each prince of the Holy Roman Empire

-

- The papal bull by Pope Leo X threatening Martin Luther with excommunication for his “heretical” 95 theses

-

- The coronation document of Otto I

-

- Documents of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

-

- Original building plans for Cologne Cathedral

-

- The original version of the German Constitutional Law

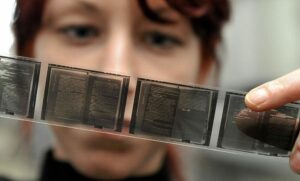

The entire complex is buried under 400 metres of rock and is fully capable of surviving a nuclear war which means the records are as safe as possible from any external threats but what they cannot be protected from as easily, is time. But with the right storage conditions we can stretch the life of microfilm into the centuries. Once the film is spliced together, it is then packed into airtight stainless-steel containers, sealed at 35% relative humidity, and then kept in a climate-controlled chamber at a constant 10ºC (50ºF). Experts believe these perfect conditions will guarantee at least a 500-year shelf life for the contents inside.

Why Microfilm Still Matters in a Digital World?

As more of our information is stored digitally on hard drives and in the cloud, it is easy to suggest that microfilm has become an obsolete medium. But these digital files are still at risk of malicious hackers, human error, and media formats becoming obsolete.

In an article published by the BBC on the Memory of Mankind project, founder Martin Kunze discusses the importance of microfilm and how he and his team are reinventing the medium to serve our archives once again.

The project aims to save our most precious documents from a “Digital Dark Age”. Their plan is to gather the accumulated knowledge of our time on microscopically engraved “ceramic microfilm”, invented by Kunze himself. This is a very interesting step for microfilm and will certainly change the way we look at the medium but what exactly is a ‘’Digital Dark Age’’.

Kunze states:

“At a conference of space weather scientists, together with officials from NASA and the US Government earlier this year, warnings were given about the fragile nature of all this digital information. Charged particles thrown out by the sun in a powerful solar storm could trigger electromagnetic surges that could render our electronic devices useless and wipe data stored in memory drives.”

It is an unsettling prospect, but one that is not outside the realm of possibility. What he and many other organisations, like the German National Archives, understand is that digital archiving has many concerning risks that mean it cannot be relied upon completely. Furthermore, it is an ever-changing medium. If history were stored in a digital-only format, the data would have to be constantly updated to more modern and specialised formats to remain accessible.

Microfilm, however, will continue to be the ultimate failsafe — and with just a simple light source and a magnifying glass, it will remain human-readable for centuries to come.

Barbarastollen: Looking Ahead with Microfilm

The Barbarastollen stands as a powerful reminder that progress does not always mean abandoning the old. Microfilm provides resilience and simplistic qualities that may one day prove crucial in protecting humanity’s collective memory.

As discussions around the “Digital Dark Age” grow louder, it is likely that more organisations will look to follow in the footsteps of the German National Archives. By combining the accessibility of digital technology with the permanence of microfilm, we can ensure our most valuable records survive, no matter what the future brings.

If you would like to learn more about this topic and how you could begin to implement microfilm into your archive today, please don’t hesitate to contact us.