As we stand on the precipice of a new technological age, where the world gazes upward toward AI, cloud storage, and digital archiving, we must be careful not to lose our footing… or, more importantly, our data.

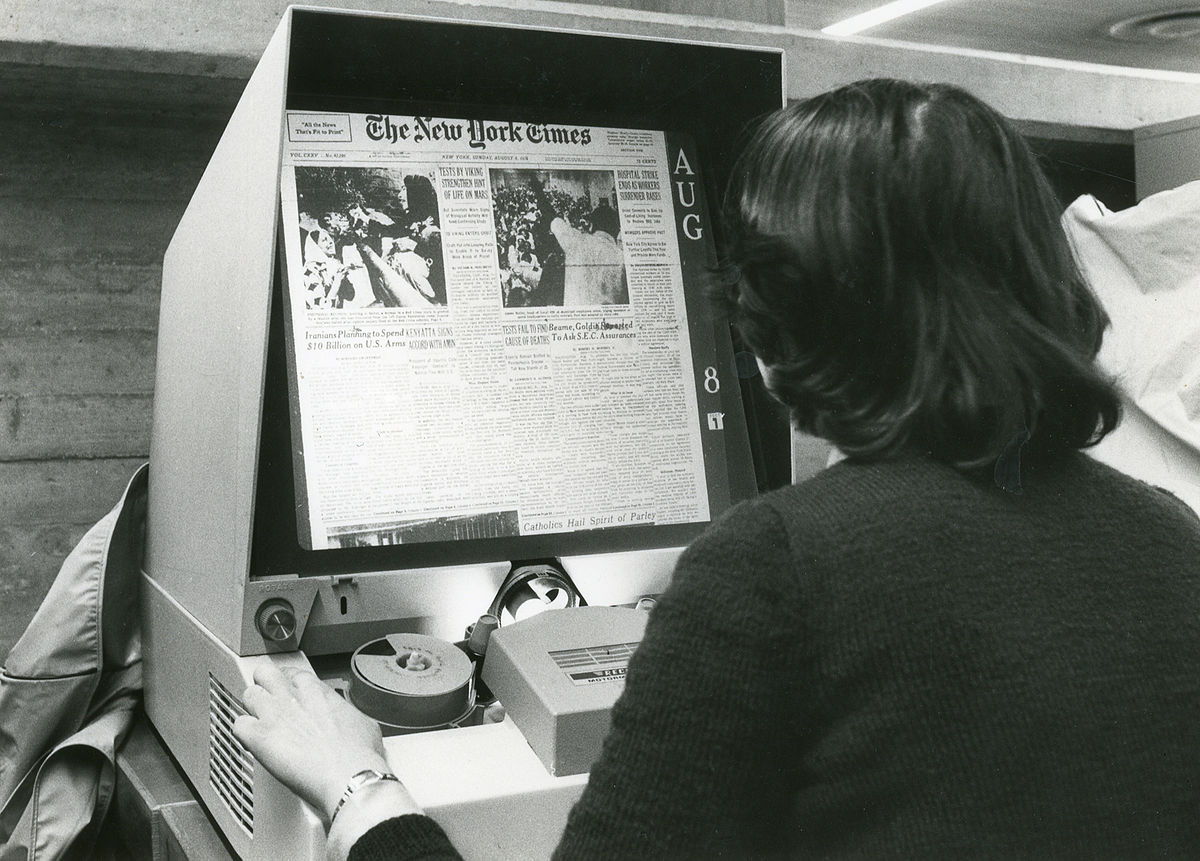

If we want to talk about the future, we must first talk about the past. So, what exactly is microfilm? Originally created in 1839 by John Dancer during the wider development of photography, microfilm’s potential wasn’t fully appreciated until the 1870s, when French optician René Dagron expanded on the original design, making it more functional. In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, he famously used microfilm messages delivered by carrier pigeon. Later, microfilm became commercially available for less dramatic uses, revolutionizing the way librarians, archivists, governments, and journalists alike stored information.

It is worth noting that in the 1960s these industries were undergoing the challenges of a phenomenon called an “Information Explosion,” where a flood of new data such as publications, governmental certificates, and legislative documents were making it increasingly difficult for companies and institutions to manage their daily operations with the sea of paper-form data that had to be waded through. It is thanks to Microfilm we were able to stay afloat. It meant Safe and convenient preservation of everything from nuclear power plant records to historical manuscripts using only a fraction of the space and with far less risk of content decay. Over time, however, the use of microfilm took a back seat while the digital age came into the spotlight. But as the digital age took centre stage, new problems emerged, and it is now time to readdress the function microfilm has in a world of cloud storage.

The Digital Dilemma

1. Losing Our Past by Chasing the Future?

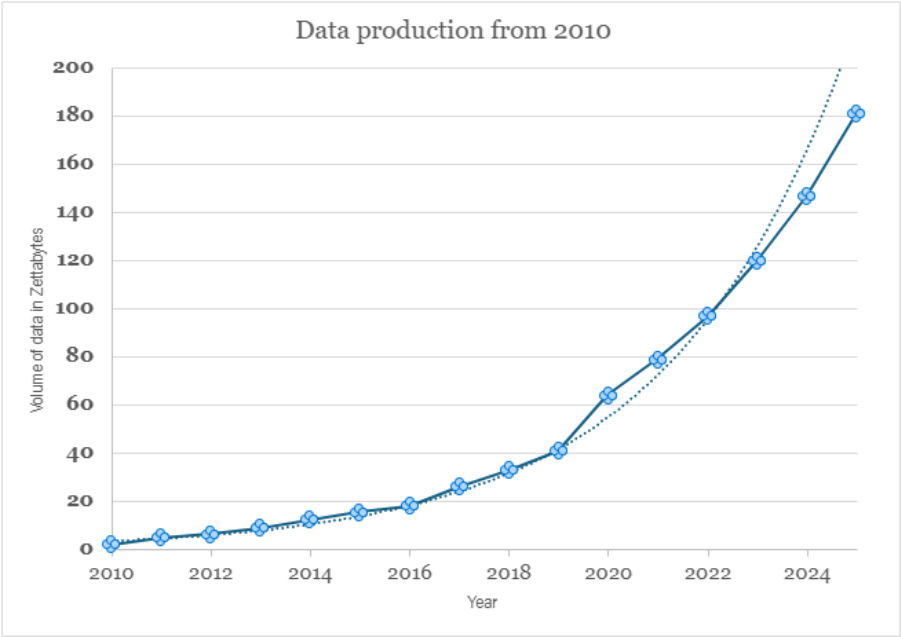

It can be argued that we may be seeing a repeat of the “information explosion” in a modern context. This year alone we have a projected production of 181 zettabytes of worldwide data; to put that into perspective, in 2010 we produced only 2. This number is expected to skyrocket in the coming decade as AI Data Centres Set to Surge. Naturally, we must develop new and more capable formats to store and manage this data, which brings into question the factor of technological obsolescence.

It is a major concern that in the coming decades we may see the emergence of what some archivists refer to as a “digital dark age,” meaning the potential loss of historical information due to the rapid obsolescence of digital technologies. Unlike microfilm, digital formats are fragile. As file formats, software, and hardware become outdated, the data stored using them can become inaccessible or corrupted, creating huge gaps in our cultural and historical record.

(source: Statista, Bernard Marr & Co.)

External Threats:

There is a growing threat of cybercrime in our modern world. Every year organisations of all sizes encounter issues with losing digital data through an ever-advancing wave of cyber-attacks. During 2024 alone, it was reported that over 560,000 new cyber threats were discovered daily. But while it is the largest of these company data breaches that hear about such as the United Health Service breach in 2020, or the worldwide Microsoft attack of 2017. In the UK 81% of businesses that suffer from cyber security attacks are in fact the much more vulnerable small to medium-sized businesses.

Ransomware is especially destructive: where attackers encrypt or steal critical files and hold them hostage. One more high-profile case reported by the BBC describes A Ransomware gang destroyed a 158 year-old company putting 700 people out of work. But there are many cases of which we hear nothing about where livelihoods and business are ruined overnight. These constant and daily attacks only take one weak password or slightly out-of-date virus protection software to make your critical data vulnerable.

Microfilm, by contrast is an analogue technology and therefore cannot be hacked, encrypted, or remotely deleted.

The Internet Is Not Forever

We often assume digital data is permanent, but the simple truth is that it isn’t.

-

- Recordable CDs and DVDs last only 5–10 years.

-

- Hard disks may last 20–30 years at best.

-

- Cloud data, though convenient, is ultimately tied to corporations, servers, and subscription models that may not exist in 50 years.

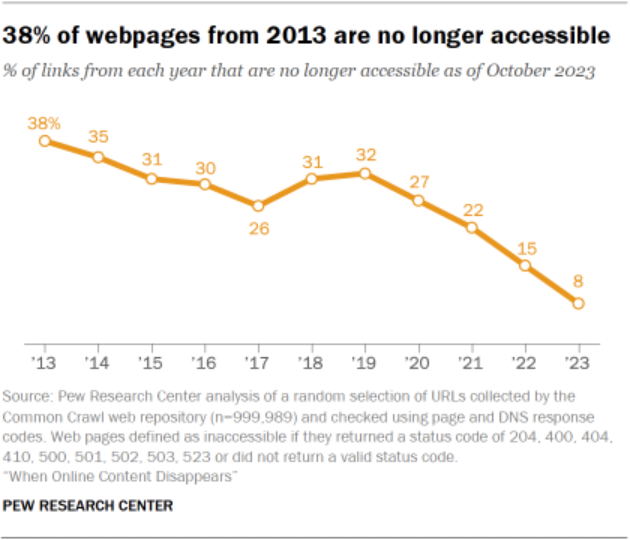

This digital/online data is vulnerable to digital decay: the slow, insidious degradation, corruption, or outright disappearance of digital files and assets. It can take many forms—such as “bit rot,” where stored data subtly degrades, or “link rot,” where once-working web addresses lead only to dead ends. Pew Research Center states that “A quarter of all webpages that existed at one point between 2013 and 2023 are no longer accessible.” For older content, this trend is even starker.

In 2021, both Google and Facebook urged the global developer community to address the escalating problem of silent data corruption—errors in stored or processed data that occur without detection, often spreading through entire systems before anyone notices.

In contrast, properly stored microfilm has an ISO 18901:2010 approved 500-year LE (Life Expectancy) rating. It is readable with nothing more than light and magnification. The ability to be easily scanned back into a digital platform as and when the archival information is required for distribution is another key feature. To put it simply: it is safe, durable, and, being an older technology, relatively inexpensive.

Digital Access, Analogue Security

None of this is to say that digital archives are useless. They are indispensable, and the advantages cannot be ignored. However, it is the case that some data is simply too valuable to be left vulnerable to the risks that digital storage has.

What we suggest is getting the best of both worlds: a microfilm-digital hybrid archiving system. Digital for access, microfilm for preservation. With this approach, you receive all the convenience, streamlined workflows, and sharing abilities of digital, as well as the longevity, security, and stability of microfilm.

This is not a hard thing to achieve, with microfilm already serving as a well-established bridge technology in digitisation, like two-way street where digital files can be written directly to a microfilm drive for automatic conversion of digital files into an analogue version on machine-readable microfilm, and vice versa.

What many once dismissed as an obsolete medium is being reinvented. Sometimes the oldest tools can be the most reliable, and in the case of modern preservation, microfilm remains just as vital to preserving our collective memory today as it did in the past.

If this topic interests you and you would like to read about a notable example of microfilm being used in archives, feel free to check out our other blog post on how Germany uses microfilm to protect its cultural heritage

Similarly, if you would like to begin implementing microfilm in your archiving system, not only do we sell the equipment to write your digital images to microfilm, but we also offer a Digital to Microfilm Service in which we can carry out the process on your behalf. This is especially popular among those with smaller collections that don’t justify the investment into equipment. And if it’s microfilm itself, you’re after, we are the distributor for Fujifilm microfilm products in the EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) region – here.

References:

-

- Debunking the Myth of Obsolescence: Strategies for Digital Heritage Conservation Li Chuqiu

-

- Digital Dark Age: Information Explosion and Data Risks March 23, 2015 by Ashiq JA

-

- Weak password allowed hackers to sink a 158-year-old company Richard Bilton

-

- Loss in the 21st Century: Digital Decay and the Archive James Boyda

-

- The Role of Microfilm in Digital Preservation

Paul Negus Heather Brown , John Baker , Walter Cybulski , Andy Fenton , John Glover , and Jonas Palm

-

- DIGITAL OBSOLESCENCE.Deljanin, Sandra

(Photo: University of Haifa Younes & Soraya Nazarian Library/CC BY-SA 3.0)